NB: People argue that the Doctor’s marriage (at least one; to Miss Mary Morstan) is canon.

For the sake of this argument, it has to be assumed Holmes and Watson were two real people and Sir ACD merely their editor.

(The cases are sorted chronologically, by the way.)

The Noble Bachelor, 1887

It is set in 1887, but it is supposed to be “a few weeks” before Watson’s marriage. Either Watson was married before Mary Morstan, but that would mean that he married this potential wife in 1887, that she died in the course of that year, and that Watson remarries in early 1889 after meeting Mary in 1888. Which does not sound too logical. Or somebody just got the dates wrong (by no means unlikely, this is Watson writing). Still, it does not really “do” for a husband to forget the year in which he was married…

The Five Orange Pips, 1887

My wife was on a visit to her mother’s, and for a few days I was a dweller once more in my old quarters at Baker Street.

First, wrong year again. Secondly, the reason why Mary came to Holmes for help was that she was orphaned and thus alone in the world. So Watson does not only forget his wedding date, but his wife’s family relations as well. Or Mary tricks him into thinking that she is visiting a nonexistent mother and is instead having an affair. Which, again, shows how much Watson was paying attention (not): if it is an excuse, it is possibly the worst I have ever heard. Or Mary does not exist at all and Watson just invented a wife when he needed to remind the readers that he was married. Anyway, this does not bode well for Mary’s importance.

The Sign of Four, 1888

Mary Morstan, an orphan, first appears in The Sign of Four, where she is introduced as a client. She has lost her father in 1878 and is now appealing to Holmes’s help. In the course of the case, Mary looses a treasure she had claims on, but gains a husband instead; Watson almost immediately proposes to her.

Miss Morstan entered the room with a firm step and an outward composure of manner. She was a blonde young lady, small, dainty, well gloved, and dressed in the most perfect taste. There was, however, a plainness and simplicity about her costume which bore with it a suggestion of limited means. The dress was a sombre grayish beige, untrimmed and unbraided, and she wore a small turban of the same dull hue, relieved only by a suspicion of white feather in the side. Her face had neither regularity of feature nor beauty of complexion, but her expression was sweet and amiable, and her large blue eyes were singularly spiritual and sympathetic. In an experience of women which extends over many nations and three separate continents, I have never looked upon a face which gave a clearer promise of a refined and sensitive nature.

After the first interview:

I sat in the window with the volume in my hand, but my thoughts were far from the daring speculations of the writer. My mind ran upon our late visitor — her smiles, the deep rich tones of her voice, the strange mystery which overhung her life. If she were seventeen at the time of her father’s disappearance she must be seven-and-twenty now — a sweet age, when youth has lost its self-consciousness and become a little sobered by experience.

Now, if you do not believe in love at first sight, this might be interesting because a popular and by no means unlikely theory is that Watson invented a wife (or more) to keep the readers from wondering. (Good luck with that.)

The Crooked Man, 1888

One summer night, a few months after my marriage, I was seated by my own hearth smoking a last pipe and nodding over a novel, for my day’s work had been an exhausting one. My wife had already gone upstairs, and the sound of the locking of the hall door some time before told me that the servants had also retired. I had risen from my seat and was knocking out the ashes of my pipe when I suddenly heard the clang of the bell.

I looked at the clock. It was a quarter to twelve. This could not be a visitor at so late an hour. A patient, evidently, and possibly an all-night sitting. With a wry face I went out into the hall and opened the door. To my astonishment it was Sherlock Holmes who stood upon my step.

“Ah, Watson,” said he, “I hoped that I might not be too late to catch you.”

“My dear fellow, pray come in.”

“You look surprised, and no wonder! Relieved, too, I fancy! Hum! You still smoke the Arcadia mixture of your bachelor days then! There’s no mistaking that fluffy ash upon your coat. It’s easy to tell that you have been accustomed to wear a uniform, Watson. You’ll never pass as a pure-bred civilian as long as you keep that habit of carrying your handkerchief in your sleeve. Could you put me up tonight?”

“With pleasure.”

“You told me that you had bachelor quarters for one, and I see that you have no gentleman visitor at present. Your hat-stand proclaims as much.”

“I shall be delighted if you will stay.”

So, Watson is exhausted, but instead of joining Mary in bed, he is essentially hiding from her. And although he is supposedly exhausted and does not like the prospect of being kept up all night, Watson sees Holmes and although he has myriad experience with Holmes keeping him up all night (no pun intended), he is “delighted”.

The Second Stain, 1888

Although it is set in autumn, there is no mention of the wife. So I suppose her loving husband just forgot her.

The Boscombe Valley Mystery, 1888

Note: this is probably set just after the marriage

We were seated at breakfast one morning, my wife and I, when the maid brought in a telegram. It was from Sherlock Holmes and ran in this way:

Have you a couple of days to spare? Have just been wired for from the west of England in connection with Boscombe Valley tragedy. Shall be glad if you will come with me. Air and scenery perfect. Leave Paddington by the 11:15.

“What do you say, dear?” said my wife, looking across at me. “Will you go?”

“I really don’t know what to say. I have a fairly long list at present.”

“Oh, Anstruther would do your work for you. You have been looking a little pale lately. I think that the change would do you good, and you are always so interested in Mr. Sherlock Holmes’s cases.”

Translation: Let us assume Mary actually exists for the sake of this argument. Watson has been married for maybe a month, and he is already looking ill. Why? Because he is locked up with his wife instead of being with Holmes. Watson’s health is getting so desperate that his wife literally begs him to meet Holmes for what appears to be a romantic holiday in rural England. (“Air and scenery perfect” - really, Holmes?)

A Scandal in Bohemia, 1889

I had seen little of Holmes lately. My marriage had drifted us away from each other.

Well, if you want to convince yourself so much… However, fact is that on his way back home from a patient, he just so accidentally ends up on Holmes’s doorstep (probably not for the first time) and is seized with a keen desire to see Holmes again. Make what you want of that.

The Stockbroker’s Clerk, 1889

Shortly after my marriage I had bought a connection in the Paddington district.

[…]

I was too busy to visit Baker Street, and he seldom went anywhere himself save upon professional business. I was surprised, therefore, when, one morning in June, as I sat reading the British Medical Journal after breakfast, I heard a ring at the bell, followed by the high, somewhat strident tones of my old companion’s voice.

“Ah, my dear Watson,” said he, striding into the room, “I am very delighted to see you! I trust that Mrs. Watson has entirely recovered from all the little excitements connected with our adventure of the Sign of Four.”

“Thank you, we are both very well,” said I, shaking him warmly by the hand.

“And I hope, also,” he continued, sitting down in the rocking-chair, “that the cares of medical practice have not entirely obliterated the interest which you used to take in our little deductive problems.”

“On the contrary,” I answered, “it was only last night that I was looking over my old notes, and classifying some of our past results.”

Long story short, a newly married man spends his time writing about his platonic best friend. Right. Watson is in a state because he cannot be with Holmes as often as he would like and so tries to evoke his “spirit” by writing about him. Does this sound like he married the right person?

The Man With The Twisted Lip, 1889

One night — it was in June, ’89 — there came a ring to my bell, about the hour when a man gives his first yawn and glances at the clock. I sat up in my chair, and my wife laid her needle-work down in her lap and made a little face of disappointment.

“A patient!” said she. “You’ll have to go out.”

I groaned, for I was newly come back from a weary day.

We heard the door open, a few hurried words, and then quick steps upon the linoleum. Our own door flew open, and a lady, clad in some dark-coloured stuff, with a black veil, entered the room.

“You will excuse my calling so late,” she began, and then, suddenly losing her self-control, she ran forward, threw her arms about my wife’s neck, and sobbed upon her shoulder. “Oh, I’m in such trouble!” she cried; “I do so want a little help.”

“Why,” said my wife, pulling up her veil, “it is Kate Whitney. How you startled me, Kate! I had not an idea who you were when you came in.”

“I didn’t know what to do, so I came straight to you.” That was always the way. Folk who were in grief came to my wife like birds to a light-house.

“It was very sweet of you to come. Now, you must have some wine and water, and sit here comfortably and tell us all about it. Or should you rather that I sent James off to bed?”

Later, after he has found Whitney in that opium den and Holmes too:

It was difficult to refuse any of Sherlock Holmes’s requests, for they were always so exceedingly definite, and put forward with such a quiet air of mastery. I felt, however, that when Whitney was once confined in the cab my mission was practically accomplished; and for the rest, I could not wish anything better than to be associated with my friend in one of those singular adventures which were the normal condition of his existence.

Watson will spend the next night in a single room with Holmes somewhere outside of London and his wife will not get to see him for some time. Also, I could simply paste in what I wrote above; the upshot of it being that a tired Watson immediately stops being tired and listless as soon as he gets out of his wife’s company and sees Holmes. Well…

Oh, and has anyone noticed that Mary calls John Watson “James”? This is where they got the “Hamish” from (he is called John H. Watson, and he is probably Scottish, and “Hamish” was “James” in Scotland). Or Mary is cheating on our doctor with a man called James and Watson does not notice, for crying out loud.

The Naval Treaty, 1889

The July which immediately succeeded my marriage was made memorable by three cases of interest

[…]

My wife agreed with me that not a moment should be lost in laying the matter before him, and so within an hour of breakfast-time I found myself back once more in the old rooms in Baker Street.

[…]

Watson and Percy Phelps return to London, while Holmes investigates on. And they do not go to Watson’s, but to Baker Street, although Mrs Watson is in town. And on the following morning: It was seven o'clock when I awoke, and I set off at once for Phelps’s room, to find him haggard and spent after a sleepless night. His first question was whether Holmes had arrived yet.

First, breakfast-time with his wife does not seem particularly important to our dead doctor. Moreover, he is so engrossed in Holmes’s case that instead of returning to his own home and comfortable bed, he stays in the Baker Street living room or Holmes’s bedroom for the night because it is clearly stated that Percy sleeps in the “spare bedroom”, i.e. Watson’s old room. Either he cannot face his wife, or – as said before – he has by now forgotten that he created one. Which is by no means uncommon for Watson; he often mentions his wife in the first paragraph and then immediately forgets her, spending the after-case time with Holmes as well. (For an example, see immediately below.)

The Dying Detective, 1890

Holmes fakes illness for a case, and Mrs Hudson goes to warn Watson:

I listened earnestly to her story when she came to my rooms in the second year of my married life and told me of the sad condition to which my poor friend was reduced.

[…]

I was horrified for I had heard nothing of his illness. I need not say that I rushed for my coat and my hat.

[…]

And the ending of the case is such: Holmes suggests that When we have finished at the police-station I think that something nutritious at Simpson’s would not be out of place.

So Watson just runs off without remotely thinking about alerting his wife or anything, and then lets Holmes take him out on a date. Watson either is not married, or he does not care all that much. Which I personally would not believe Watson is callous enough for.

The Blue Carbuncle, 1890

It all starts with Watson coming to Baker Street on Boxing Day: I had called upon my friend Sherlock Holmes upon the second morning after Christmas, with the intention of wishing him the compliments of the season.

But the story ends with him staying for a Christmas dinner. Holmes says: If you will have the goodness to touch the bell, Doctor, we will begin another investigation, in which, also a bird will be the chief feature.

Do you not have a wife to return to, doctor?

The Final Problem, 1891

It may be remembered that after my marriage, and my subsequent start in private practice, the very intimate relations which had existed between Holmes and myself became to some extent modified.

[…]

“I must apologise for calling so late,” said he, “and I must further beg you to be so unconventional as to allow me to leave your house presently by scrambling over your back garden wall.”

“But what does it all mean?” I asked.

He held out his hand, and I saw in the light of the lamp that two of his knuckles were burst and bleeding.

“It is not an airy nothing, you see,” said he, smiling. “On the contrary, it is solid enough for a man to break his hand over. Is Mrs. Watson in?”

“She is away upon a visit.”

“Indeed! You are alone?”

“Quite.”

“Then it makes it the easier for me to propose that you should come away with me for a week to the Continent.”

“Where?”

“Oh, anywhere. It’s all the same to me.”

Watson’s nonexistent wife is nonexistent. The luck he has that she is always visiting random people… (And if you are interested, there is no reason whatsoever to go anywhere. Holmes only wants Watson on another romantic holiday, this time in the Alps.)

The Empty House, 1894

In some manner he had learned of my own sad bereavement, and his sympathy was shown in his manner rather than in his words. “Work is the best antidote to sorrow, my dear Watson,” said he, “and I have a piece of work for us both to-night which, if we can bring it to a successful conclusion, will in itself justify a man’s life on this planet.” In vain I begged him to tell me more. “You will hear and see enough before morning,” he answered. “We have three years of the past to discuss. Let that suffice until half-past nine, when we start upon the notable adventure of the empty house.”

And that is the last we will ever hear of Watson’s wife.

Incidentally, it has been suggested that Mary 1) died, 2) divorced, or 3) was arrested. How could that be? Well, here is an interesting quotation from Holmes:

“My collection of M’s is a fine one,” said he. “Moriarty himself is enough to make any letter illustrious, and here is Morgan the poisoner, and Merridew of abominable memory, and Mathews, who knocked out my left canine in the waiting-room at Charing Cross, and, finally, here is our friend of to-night [Moran].”

I.e.: Ms are evil. Morstan…

The Norwood Builder, 1894

At the time of which I speak Holmes had been back for some months, and I, at his request, had sold my practice and returned to share the old quarters in Baker Street. A young doctor, named Verner, had purchased my small Kensington practice, and given with astonishingly little demur the highest price that I ventured to ask—an incident which only explained itself some years later when I found that Verner was a distant relation of Holmes’s, and that it was my friend who had really found the money.

No mention of his wife’s death – only of Holmes’s return. Which also suggests that Mary did not in fact die but was either killed off by Watson or they got divorced, depending on which theory you favour. And, by the way, it means that Holmes is prepared to spend a fortune on Watson’s return to Baker Street without telling him. This is very sweet.

The Blanched Soldier, 1903

I find from my notebook that it was in January, 1903, just after the conclusion of the Boer War, that I had my visit from Mr. James M. Dodd, a big, fresh, sunburned, upstanding Briton. The good Watson had at that time deserted me for a wife, the only selfish action which I can recall in our association. I was alone.

This is Holmes speaking of a wife who will never be mentioned again and even though I will not enter into all the subtext that is in the two stories narrated from Holmes’s perspective, let it just be said that there are some real doubts regarding his retiring alone. (Big surprise.) The story has a huge gay subplot that I have explained already, which could hint at the gay plot that is also going on, although Holmes and Watson have to take precautions because they have got the people talking again…

In conclusion:

There are two theories too choose from: That Watson was indeed married but that he was not interested in his wife at all, which enabled her to have affairs, lie to him etc, or that Watson invented Mary as a necessary plot device.

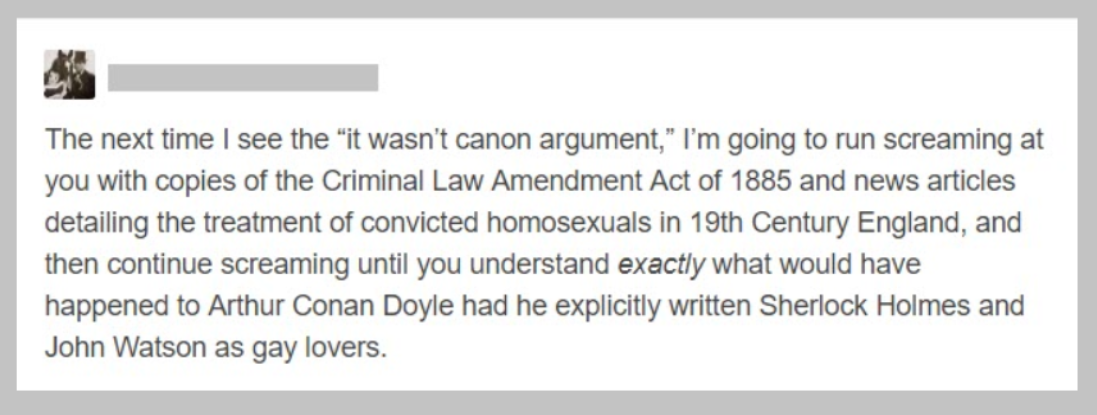

Personally I believe in the second theory for the following reasons: In the first story (A Study in Scarlet), Watson does not show much interest in women, and in The Sign of Four, Sir ACD (or the doctor himself) saw the necessity to establish Dr Watson as a heterosexual married man to avoid rumours about a potential “deviant” relationship between Holmes and Watson. So a wife was invented, presented as absolutely lovely during in The Sign of Four, and is then literally made to disappear. After her first appearance, she never so much as says more than three sentences in a row. The author clearly did not make much effort creating Mary Morstan’s character, which can be concluded from several facts, icluding the one that we do not even know how Mary dies. Or if.

But be as it may: do you really get the impression that the doctor cared at all about this wife of his?