Saved Archived Meta: Weeesi (pt0)

Dec. 6th, 2015 07:45 pmMeta

Currently a wip: I’ll be updating this page regularly.

*************************************************************************************************************

I Read Books and Write About Them:

Nameless Offences: Homosexual Desire in the 19th Centuryby H.G. Cocks

London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914 by Matt Cook

- Empty train carriages, Molly houses, and moustaches on trial

- “That’s not a sentence you hear every day” - how modern Sherlock incorporates Victorian-era facial hair code

- Gay lit is gay, the Criterion bar is gay, Turkish baths are gay, green carnations are gay, button holes are gay

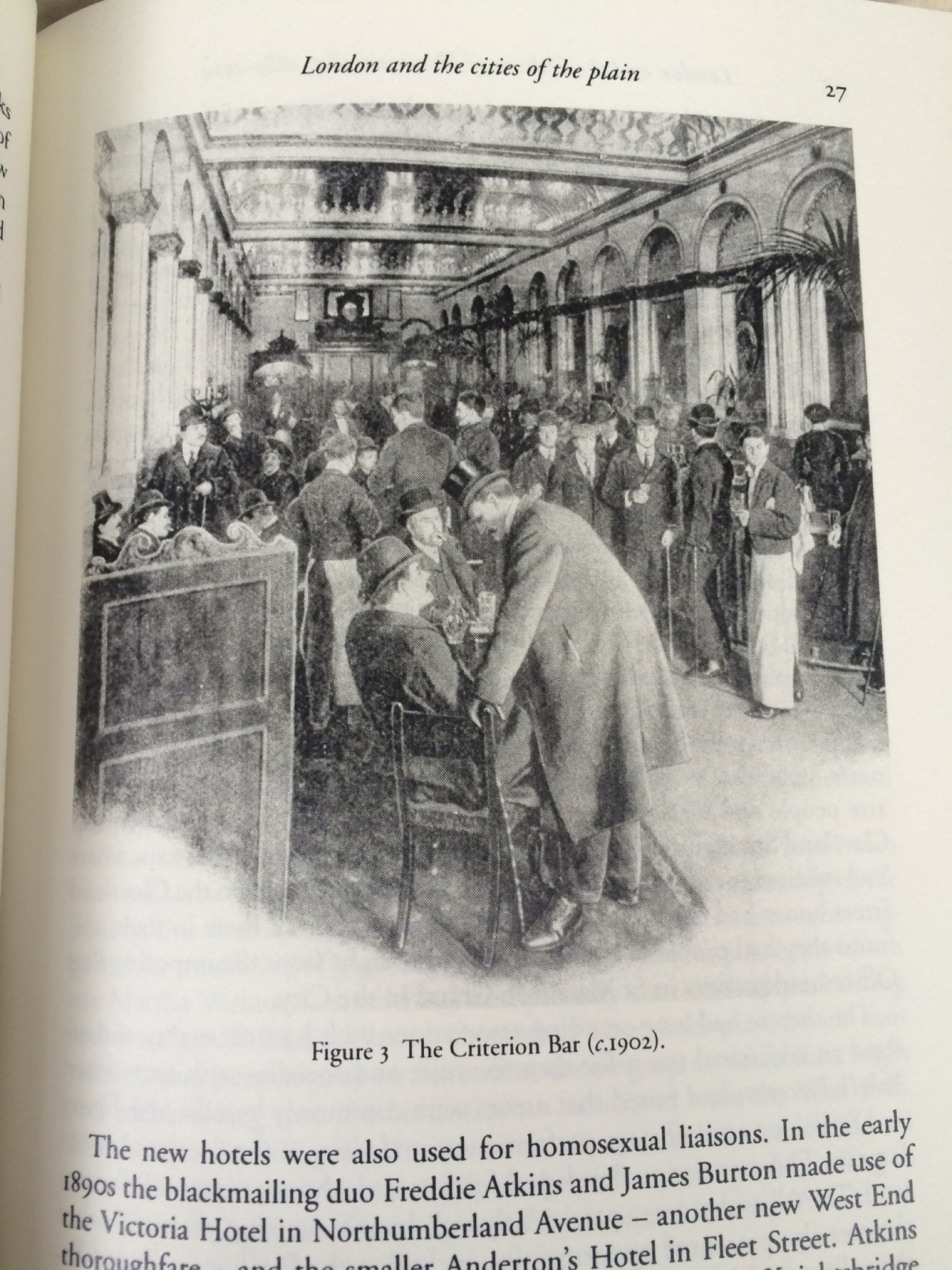

- Homosexual men loved to liaise at the Criterion Bar

- TJLC is Real: Carefully-Chosen Words and Public Opinion

- Sherlock fits a case study of a period-relevant homosexual man

- Anal violins

- Gay graffiti worth writing about in your memoirs

- Cabs were helpful, Gothic romance was queer, literary gay subtext was criminal evidence, the male-on-male gaze was a stand-in for sex, and idealised male nudes were all the rage

- Every Great Cause Has Martyrs - how language used in the TAB trailer mirrors that used by Victorian homosexual men

- Did Victorian-Era Gay Men Think Sherlock Holmes Was Gay?

- The closest thing I’ve ever written to a personal TJLC manifesto

Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century by Graham Robb

- What ACD said about Oscar Wilde, how do you know if you have homosexual “characteristics”, and why the colour green is gay

- Turkish bathhouses, the Achilles statue, and my dear boy

- Lifting the veil, coded meanings, and red neckties/handkerchiefs

- Gay marriages took place in secret in the 19th century

- Knee gropes and “crude symptoms of physical sexual sympathy”

- Homosexuality in Victorian literature, Part 1

- Homosexuality in Victorian literature, Part 2

- Sherlock Holmes and Victorian Homosexuality – original post

- Sherlock Holmes and Victorian Homosexuality – with extended material on ACD, authorial intent, and Hellenic influences on 19th century gay culture

*Sherlock’s Men: Masculinity, Conan Doyle, and Cultural History by Joseph Kestner

- Arthur Conan Doyle and Subtext

- ‘I only saw it because I was looking for it’: Here We Go Again, aka parallels between the “urban homosexual” and the “private detective” in the late nineteenth century

- Mary is American

- First impressions of the book

*Arthur Conan Doyle and the Meaning of Masculinity by Diana Barsham

*in progress

*************************************************************************************************************

BBC Sherlock Meta:

TAB:

- A Very Charming Habit

- drink code

- Sherlock’s worst nightmare

- um did you mean by using subtext?

- look how Mary is holding her arms

- What made you like this? (pre-airing)

- Abominable is a Very Important Word (pre-airing)

- Fear is wisdom in the face of danger (pre-airing)

Others:

- John straddled Sherlock and the Ds touched on the Reunion™ night

- this is exactly what John wants, and this is also why John stayed with Mary

- Irene flirted with Sherlock to make John jealous

- why do David and Sholto exist

- literally the two people closest to John betrayed his trust

- why did Mary wear her perfume that night?

- how long did John listen to Sherlock have fake bathtub sex

- Harry’s Short for Harriet

- one of the reasons Sherlock didn’t tell John he was going to jump

- arse-up during stag night

- alternate episode titles/six-word stories

Sherlock Holmes and Victorian Homosexuality

[This is the final post in my series on Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century by Graham Robb. Previous posts can be found here.]

Dearest friends. Dear sweet ones. Dear softest lambs. Prepare yourselves.

Robb’s last chapter is on literature and literary references to homosexuality.

And he chooses to talk – at length – about Sherlock Holmes and John Watson.

He writes:

The following observations are not a sly attempt to ensnare the great detective in the elastic web of gay revisionism. Everyone already knows, instinctively, that Holmes is homosexual.

Well then.

If there is one post you read from this series, it should be this one.

First, Robb includes a brief analysis of earlier detective characters, such as Poe’s Dupin, of whom he writes this little nugget:

There is, of course, nothing essentially odd about the passionate, secretive and nocturnal friendship of two strange men in a crime-ridden city, even if one of them is a dandy with a “diseased” mind and the other…finds a muscle-bound sailor…”not altogether unprepossessing.”

and notes that as of the mid-1800s, even fictional references to two men “keeping the shutters closed” while at home together sounded suspicious.

Quite the precursor to johnlock vibes, no?

It gets better.

Robb begins his discussion of Holmes and Watson by examining previous adaptations of ACD’s stories, including whether or not Holmes was coded as homosexual:

Screen adaptations are a good test. The least convincing are always those that provide him with a girlfriend. The most convincing, like Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) – promoted as “a love story between two men” – are those that exaggerate his camp behaviour. Without the tense, suppressed passion that binds him to his biographer, Holmes is just a man with an interesting hobby.

(Click on the link to see Martin basically saying that exact same thing.)

Excuse me while I restart my heart.

Arthur Conan Doyle

Robb remarks that “Conan Doyle himself was quietly ambivalent on the subject of homosexuality” but had once requested information on sexual perversion (aka it means what you think it means) from a gay man (Roger Casement) whom ACD later publicly supported when Casement’s own homosexuality was revealed.

ACD was also supportive of Oscar Wilde, and Robb argues that “Holmes himself bears a striking resemblance to Oscar Wilde.” Doyle first met Wilde in August 1889, after which Wilde wrote and published The Picture of Dorian Gray, “a book which is surely upon a high moral plane,” according to Doyle. Other reviewers thought it obviously homoerotic and said it was unsuitable for anyone other than “outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys” – the book was later used as evidence against Wilde in his trial. Likewise, Doyle wrote and published The Sign of Four after their meeting. Even 35 years later, Doyle well remembered “that golden evening” during which Wilde had made an “indelible impression” upon him.

doesn’t that sound like John talking about meeting Sherlock in ASiP

“Queer”

Robb analyses many character traits that Holmes shares with other aesthetes of his era (who were often homosexual) and also notes the unique qualities of his brother Mycroft Holmes, who spends time at the Diogenes Club, “the queerest club in London, and Mycroft, one of the queerest men.”

Yes, but queer?

According to Robb’s research, in 1894, “queer” had already acquired its modern sense. Oscar Wilde’s prosecutor, the Marquis of Queensberry, had referred that year to “the Snob Queers like Roseberry” [sic]. The words “earnest” and “languid”, used in other stories and applied to Holmes, also had homosexual connotations during that time period.

Relationship with Watson

Robb notes that “the only woman [Holmes] admires is Irene Adler, who dresses as a man” during ACDcanon ASiB. In every other sense, the “softer human emotions” in Holmes are reserved entirely for Watson.

Sorry, need to restart my heart again.

In the stories, Holmes tries to display partner (read: wifely) qualities such as preparing dinner (a meal of grouse and oysters) and showcasing a lovely bedside manner (lulling Watson to sleep by playing violin). Sadly, Watson doesn’t leave Mary and Holmes loses him with “a most dismal groan.”

Robb writes:

Happily, Mrs. Watson never materialises and has the grace to be dead by 1904. “Old times” return, with many moments of fervent intimacy: Watson’s hands are clutched, his knees patted, and his ears brushed by Holmes’s whispering lips. When the trail leads out of London, they sleep in “double-bedded” rooms.

Then he quotes Garridebs, which I just literally cannot at this point.

Basically, “the 19th-century man of forensic investigation meets the 19th-century man of medicine in a loving embrace” after the wound is noticed and dear god, save us all from this hell.

Public Perceptions

Robb considers that “a writer who could tease his readers with untold tales like that of the Giant Rat of Sumatra (”for which the world is not yet prepared”), was certainly capable of toying with the subscribers of The Strand Magazine and their amazing infatuation with Holmes.” Um, come again?

ARE YOU SAYING ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE DID THE SAME THING WITH THE STRAND PEOPLE AS MOFFTISS HAVE DONE WITH US

*shakes fists at the sky*

Sherlock Holmes

TW: implied underage sexual relations in the very next paragraph, skip to second paragraph to avoid

Holmes “trains a gang of little urchins and in The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901) adopts a fourteen-year-old telegraph boy as his valet, which was hardly an innocent act after the Cleveland Street scandal”. This had occurred some years earlier and involved young telegraph boys who worked as prostitutes for older, wealthy men. Robb notes that Holmes’ pack of boys not only help out with errands but also “fill up the gap of loneliness and isolation” which sometimes clouded Holmes – implying perhaps some other relationship beyond casework. This casual reference would not have been missed.

Robb argues that Holmes’ sexuality is “an essential part of his character”. He has a “distinctly homosexual lifestyle” in the stories:

- he goes to the Northumberland Avenue Turkish baths with Watson, of which Watson says they both “have a weakness”

- he is said to read things which had homosexual connotations at the time, including Horace, Catullus, Hafiz, and Thoreau; anthropology, medicine, scandal sheets and police records

- he goes to Chinese opium dens, hangs out with “rough-looking men”, and changes his personality/appearance at will (including dressing as a woman) based on what part of London he is visiting

All of these were things that were attached to real or fictional homosexual men in the late Victorian-era.

Connection to Victorian Laws and Scandals

Holmes first appears in print two months after the Labouchere Amendment which made gross indecency a crime. He also appeared in February 1890, during the fevered publicity of the Cleveland Street scandal. He asks Watson to run away with him to the Continent after nearly losing his life in Vere Street – another name associated with homosexual scandals. Robb also questions what we are to make of Moriarty, given the “dark rumours” that forced him to resign his university job and the “hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind” that he supposedly suffers from.

maybe because Moriarty is also coded as gay

Ultimately, Robb concludes that these too were tales “for which the world was not yet prepared.”

Conclusions

The sexually ambiguous detective and his unusually devoted companion actually appears more often than one might think in literature that came out of this time period. Robb lists several other pairings that follow this same sort of mold, although he acknowledges that it wasn’t “conscious imitation” since no one at the time outed Holmes as being homosexual, except for “casual humourists.”

Robb notes several similarities between the “urban homosexual” of the late Victorian-era and the fictional character of “private detective”:

- heightened awareness

- the wearing of masks (literally or figuratively)

- the street-wise reading of signs

- the ability to operate in different milieux

- reading the secret configurations of the city

- understanding that sexual singularity was key to a hidden world

- habit of avoiding detection

- ability to identify others who are similar

- domestic arrangements open to change

- knows how to converse with strangers

He argues that the detective figure – and the success of these stories and characters, including Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes – shows a “direct and positive influence of gay culture on the majority culture.” However, he ends with the acknowledgment that most gay men and women of this time would have been happy to exchange their literary influence for “respectability and affection,” something that was not forthcoming around the turn of the century.

Lucky for us, it’s no longer the 19th century. Here is the chance for Holmes and Watson to love each other openly. After over 100 years of being trapped between the lines, researchers and adapters are finally setting them free.