Saved Archived Meta: Weeesi (pt1)

Dec. 8th, 2010 01:17 am(Commentary by Crow: I prefer for this blog to stay as strictly focused on ACD meta as possible. Unfortunately that can not be entirely the case as there are many useful metas about the original Canon stories that are also interwoven with bbc commentary. Please forgive their addition, as their notes regarding ACD Canon itself are useful.)

London and the Culture of Homosexuality – Masterpost

1) Empty train carriages, Molly houses, and moustaches on trial

2) “That’s not a sentence you hear every day” - how modern Sherlock incorporates Victorian-era facial hair code

3) Gay lit is gay, the Criterion bar is gay, Turkish baths are gay, green carnations are gay, button holes are gay

4) Homosexual men loved to liaise at the Criterion Bar

5) TJLC is Real: Carefully-Chosen Words and Public Opinion

6) Sherlock fits a case study of a period-relevant homosexual man

7) Anal violins

8) Gay graffiti worth writing about in your memoirs

9) Cabs were helpful, Gothic romance was queer, literary gay subtext was criminal evidence, the male-on-male gaze was a stand-in for sex, and idealised male nudes were all the rage

10) Every Great Cause Has Martyrs - how language used in the TAB trailer mirrors that used by Victorian homosexual men

11) Did Victorian-Era Gay Men Think Sherlock Holmes Was Gay?

12) The closest thing I’ve ever written to a personal TJLC manifesto

Discussions/asks/misc with other people about the book: here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here

Buy the book online

Thank you to everyone who read/commented/liked/reblogged posts from my little readalong liveblog. I loved doing it and I hope you liked it too.

Up next:

Strangers: Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century by Graham Robb

------------------------

1) Empty train carriages, Molly houses, and moustaches on trial

1) Empty train cars (railway carriages) were quite popular spots for gay men to rendezvous and do the do

2) A gay man was often referred to as a “Molly” and a “Molly House” was a place where gay men could socialise together

3) A famous case involving two men (Ernest Boulton and Frederick Park) who were accused of homosexual activity and charged with “conspiring and inciting persons to commit an unnatural offence” was brought to court to great public spectacle. During their trial, one of the men (Park) GREW A MOUSTACHE to try to conform to the era’s expectations of masculinity (many men who were identified as gay were clean shaven).

“That’s not a sentence you hear every day.”

We’re all very familiar with the sort of cringe-worthy yet sweetly honest scene in TEH where Sherlock and John have this little exchange (and thanks again to Ariane DeVere’s transcripts):

SHERLOCK: See you’ve shaved it off, then.

JOHN: Yeah. Wasn’t working for me.

SHERLOCK: Mm, I’m glad.

JOHN: What, you didn’t like it?

SHERLOCK (smiling): No. I prefer my doctors clean-shaven.

JOHN: That’s not a sentence you hear every day!

John is surprised and focuses on the sentence rather than the meaning, the format instead of the content, as the viewer is supposed to do too.

Let’s back up a bit. Obviously BBC Sherlock Holmes was not created out of thin air in the 21st century – the original character was created in 1887 during the late-Victorian era. At this time it was against the law - a criminal act - to engage in homosexual activity and men who had sex and/or “improper” relationships with other men were under constant threat of being arrested and prosecuted in court, with some even sentenced to hard labour in prison.

During this time, however, many men who identified as homosexual (which in itself was a complicated concept and meant different things to different men) started to find unique ways to identify each other: for solidarity, friendship, support, sex.

I made another post talking about London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914 by Matt Cook, which is an incredible resource on queer history and culture at this time (though focuses exclusively on male homosexuality). In the book, Cook talks about various ways that men were stereotyped as homosexual: being effeminate, being a (confirmed) bachelor, a theatregoer, a dandy, wearing scent, living a “bohemian” lifestyle.

Oscar Wilde was called a bohemian repeatedly, in the press and elsewhere, during his trials. Who else was called a bohemian…oh. Sherlock Holmes was called a bohemian… by Watson himself. Here’s the quote, from A Scandal in Bohemia, published four years before Wilde’s trials:

“My marriage had drifted us away from each other. My own complete happiness, and the home-centred interests which rise up around the man who first finds himself master of his own establishment, were sufficient to absorb all my attention, while Holmes, who loathed every form of society with his whole Bohemian soul, remained in our lodgings at Baker Street, buried among his old books, and alternating from week to week between cocaine and ambition…”

Curious that you’re so happy in your marriage, Watson, yet you still refer to 221B as “our lodgings”. But I digress. We have a juxtaposition in the text: supposedly happy, hetero-married John Watson, master of his domain, describing confirmed bachelor Sherlock Holmes’ apparent depression, alone and gay in Baker Street, but clearly preferring that over the social and sexual demands of a homophobic society. For as much as he’s trying to draw the line between himself and Holmes here, Watson immediately drops everything to go out on another case with Holmes. Of course, this “bohemian” signifier is used in the story featuring Irene Adler, a woman who appears in the BBC modern verison in ASiB, an episode which focuses heavily on sex and sexual identity.

Anyway, back to the moustaches.

Being “bohemian” was just one way to identify men who were considered to be homosexual. Another was being clean-shaven. A man who was placed on trial for homosexual activity grew a moustache so as to conform to contemporary standards of heterosexual masculinity. As Cook says, “…though certainly not a definitive indication of sexual deviance, [being clean shaven] was a commonly noted feature of defendants in cases of gross indecency between men” and almost always reported in the press. He continues: “Facial hair functioned as a symbol of masculinity and respectability during…the late-Victorian ‘beard-boom.’ Those without it were associated with fashion, bohemiansim, and an avant-garde - but also possibly worse” – being a homosexual.

George Ives, a friend of Oscar Wilde’s and a gay man, shaved off his moustache on Wilde’s advice once he set himself up in the West End as an independent bachelor and decided to pursue sexual and emotional relationships with other men.

For Sherlock Holmes to be clean shaven at the end of the 19th century would definitely have signified something to the average reader who was at least slightly familiar with masculine culture in London.

Here’s some of the many Sherlock Holmes we’ve seen over the years:

What does John Watson usually look like?

In The Abominable Bride, Sherlock is clean shaven as usual, and John has a moustache, but setlock photos suggested that John has some scenes sans moustache (unless this was due to Martin just not having it on yet – we’ll have to wait and see).

The symbolism of facial hair and having it/not having it was a significant indicator of sexual preference during the era when Sherlock Holmes was at the height of his glory in late-Victorian London. Curiously, it’s also become a focus in the modern adaptation as well.

To return to that scene in TEH, Sherlock admits to John that he doesn’t like his appearance with a moustache (he doesn’t like John altering his appearance to change aspects of himself), and John admits it wasn’t working for him (can only keep up altered appearances for so long). Interestingly, he asks Sherlock to confirm “you didn’t like it”. John grew it when he thought Sherlock was dead and became engaged to a woman.

Sherlock plainly says he prefers his doctors clean-shaven. To the modern ear, this sounds weird and means nothing, really. To the late-Victorian ear, this would be nearly tantamount to saying that you prefer gay men, or that you yourself might be gay, according to popular contemporary trends and beliefs.

A clean-shaven John, especially one that does this

3) Gay lit is gay, the Criterion bar is gay, Turkish baths are gay, green carnations are gay, button holes are gay

I’ve made some more progress on the book I’m currently obsessed with, London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914 by Matt Cook, and have made a couple posts about it here and here. Now I have my next longer meta brewing (!!)…but in the meantime, here are some updates:

(if you’re not keen to see more posts like this, I’ll tag everything related to this book “london and the culture of homosexuality” so you can avoid it if you like)

1) The Sins of the Cities of the Plain was a pornographic (homosexual) novel published in 1881. It follows the memoirs of a young male prostitute, John Jack Saul, who is “paid to set down his experiences by a client“, who just happens to provide an address in Baker Street, which was really the address of a friend called William Sherlock Scott Holmes Potter. The book talks about doing the do in Belgravia and picking up men in Regent’s Park, as well as the joys of having sex with guardsmen/soldiers. It did not mess around: one of the chapters is literally called “The Same Old Story: Arses Preferred to C*nts”. So. It was pretty gay.

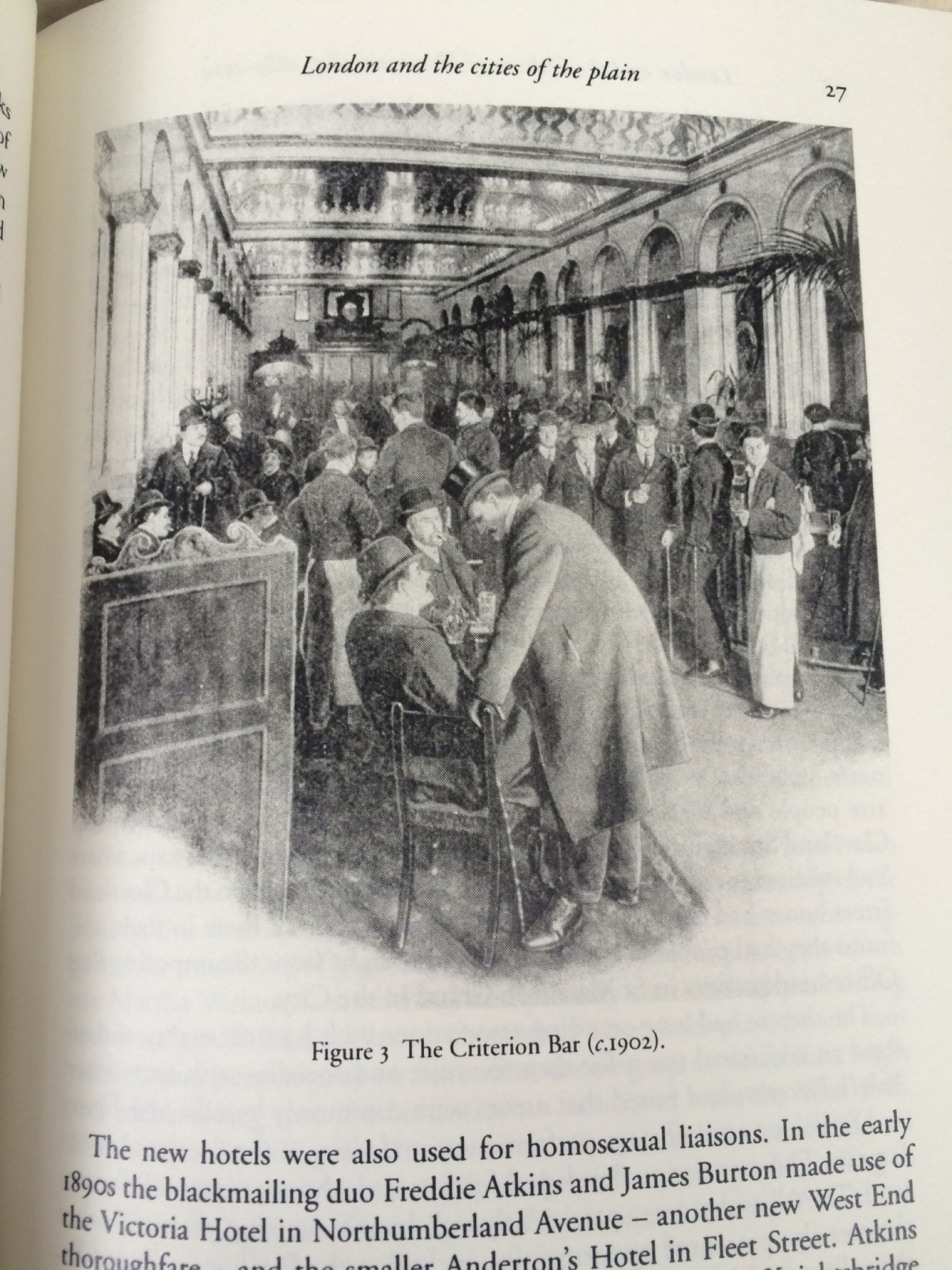

2) The Criterion Bar on Piccadilly Circus attracted all kinds of men, including guardsmen, for meetings of a more intimate nature. According to Cook’s research, it was considered to have “a subcultural reputation for homosexual activity” and was a “great centre for inverts”, according to some 19th century contemporaries. (“Invert” was another derogatory term for homosexual.) I’m sure there’s no need to remind you that this is where John Watson and Mike Stamford meet up before Stamford introduces Watson to the love of his life Holmes.

3) Turkish baths were considered to be very gay (many other homosocial spaces developed similar reputations).

4) Articles in popular fashion magazines like Modern Man “bemoaned the damage done to the fashion for buttonholes by [Oscar] Wilde’s penchant for green carnations”.

This, in an article titled: “Judging a Man by His Button Hole.”

WHAT COULD IT MEAN

----------------------------4) Homosexual men loved to liaise at the Criterion Bar

Just liaising….

(from London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885-1914 by Matt Cook)